This report concerns the village of Burqah, Ramallah District. A rather unremarkable village, Burqah has never taken center stage in the fight against the occupation, and has not been subjected to extreme punitive measures. In fact, we chose to focus on Burqah precisely because it is unexceptional, as a case in point demonstrating what life under the occupation is like for residents of Palestinian villages. It is a small, picturesque village, surrounded by fields. Like many other villages, it endures severe travel restrictions which isolate it from its surroundings. It is also subject to massive land-grabs and stifling planning, all of which have turned it into a derelict, crowded and backward village with half its population living at or below the poverty line.

Burqah residents may live in Area B, but despite the illusion created when powers were transferred to the Palestinian Authority, Israel’s full control of Area C means it has the power to influence many aspects of life in Areas A and B, even allowing it to freeze the day-to-day routine of Palestinians living in those areas:

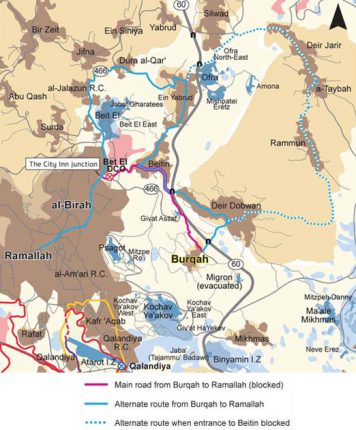

Road Closures: Early in the second Intifada, the Israeli military closed the main road from Burqah to Ramallah. The road has remained closed ever since, transforming the short trip to Ramallah from a few minutes’ ride into a 45-minute journey through winding bypass roads ill-equipped to accommodate substantial volumes of traffic. The road closures have converted Burqah into an isolated, remote village, despite its geographic proximity to Ramallah. Road closures have also limited access by Burqah residents to all the services provided in Ramallah, the district’s major urban center: employment, medical services, shopping centers, institutions of higher education and leisure facilities.

Land grab – official and unofficial: Burqah’s economy traditionally relied on farming. In the early 1980s, Israel began building settlements – Psagot, Kochav Ya’akov, Giv’at Asaf and Migron – on and near land privately owned by Burqah residents. As a result, residents’ access to land they had once farmed has been restricted. Roughly 94.7 hectares of land owned by village residents is now inside the settlements or located on the other side of the settlements’ access roads, and therefore inaccessible to its owners. About 60% of the land taken was either partially or fully cultivated. In addition, due to recurring violence on the part of the settlers in the area along with the very presence of settlers on village farmland and grazing areas, residents avoid accessing an additional area of about 128 hectares of land they own, despite the absence of any official restriction. All told, residents cannot access roughly 220 hectares of land, an area equal to about one third of village lands.

Housing shortage: Burqah’s built-up area and the small amount of farmland around it are defined under the Oslo Accords as Area B. Yet most of the village land reserves for development, as well as its vast tracts of farmland, are located in the area designated Area C. Since any construction or development in Area C involves getting approval from Israeli authorities, and such approval is virtually impossible to get, residents suffer a shortage of housing and public facilities even if they do own land.

These issues affect every aspect of life in the village. The economic situation is grim. At least half of village families with five or more members – about 75% of the total population – earn a sum that is just at or even below what is considered the deep poverty line in the West Bank (about NIS 1,800 [approx. USD 530] a month). Most of the men in the village do work, but they have no job security, and only part time positions or irregular odd jobs. In the over 52 age bracket, employment is just 50%, with only a quarter having steady jobs and working as many hours as they would like. Both men and women supplement their income by farming, shepherding, cheese making, work from home such as sewing and embroidery, but this added income is very insubstantial. Travel issues also have a detrimental effect on education and health services in Burqah: medical and teaching staff who are non-residents have to contend with obstacles in reaching the village; residents face hardships in getting to places outside the village to obtain such services.

Burqah is a case in point. Its situation demonstrates the effects of the occupation, showing how the settlements and their interests play a central role in Israel’s policy planning in the West Bank, even at the cost of grave harm to the Palestinian residents, and how a legal-administrative web stifles a village, life and development. The Israeli authorities always put the interests of the settlers and the settlements before those of the Palestinian population. Although the settlements are unlawful in themselves, Israel allocates a great deal of resources to developing them and protecting their residents, while doing everything in its power to block Palestinian development.

A real change in the situation in Burqah, and the rest of the West Bank, can only come about when the occupation ends. Even so, Israeli authorities have the power to institute several measures that would significantly improve the lives of Burqah and West Bank residents. In Burqah’s case these measures must include the following:

Removal of all checkpoints and roadblocks placed on the roads leading from Ramallah to the villages east of the city;-

Ensuring residents of Burqah are able to safely reach, cultivate and graze herds in their land located near the settlements, without fear of settler attacks;

Issuing construction permits to village residents, enabling them to build on land they own which was defined as Area C by the Oslo Accords. They must be allowed to build various types of buildings, including housing and public facilities required for village development.

العربية

العربية עברית

עברית Türkiye

Türkiye Русский

Русский Français

Français We Watch Israeli Violations Specialized website in monitoring and documenting Israeli violations against Palestinians

We Watch Israeli Violations Specialized website in monitoring and documenting Israeli violations against Palestinians